A Brief History of British Antivaccinationism and Vaccine Scepticism – Part 2, Jenner’s Critics

Introduction

This series hopes to explore the history of British Antivaccinationism and Vaccine Scepticism. It is divided into 7 main eras: the period of Inoculation, 1721-1798; the introduction of vaccination, 1798-1853; the imposition of mandates, 1853-1902; the remaining history of the National Antivaccination League, 1902-1972; DTP Vaccine Scepticism 1972-1998; Andrew Wakefield and vaccines cause autism, 1998-2019, and Covid 19, 2020 to present. This section forms part 2 looking at Jenner and his critics.

The ‘Discovery’ of Edward Jenner

In 1796, Edward Jenner performed his first vaccination. This was on an 8 year old boy called James Phipps. In this experiment, Jenner inserted into the arm of the boy matter from the teat of a cow with cowpox using a lancet. Cowpox was a disease of the cow’s udder, which caused pustules to appear on that area. It was transmitted to humans via the action of milking a diseased udder.

Jenner’s justification for doing this was that cowpox allegedly prevented smallpox. There had long been a rumour among dairy maids that they could not contract smallpox, if they had contracted cowpox. In fact, the official story or mythology of Edward Jenner states that he overheard this idea from a dairy maid when he was a teenager and was taken with testing it (this is narrated by Jenner’s sycophantic biographer, John Baron).

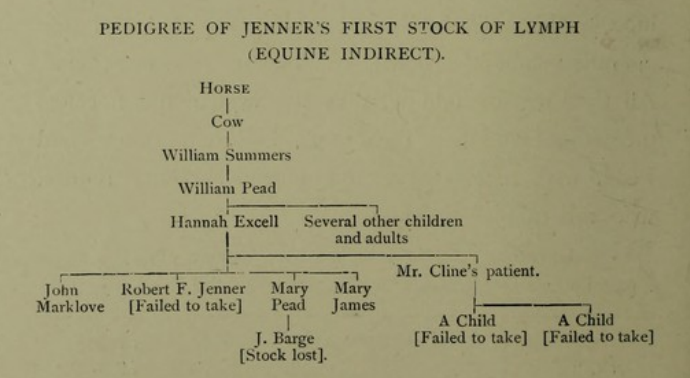

Jenner became a country doctor in Berkeley, Gloucestershire. He became a member of the Royal Society after writing a paper about cuckoos that was accepted. In 1796, when Jenner performed his first inoculation with vaccine virus (later known as vaccination) he wrote a paper outlining his theory of the origins of cowpox (he believed that it originally came from the horse, and was transferred to the cow via those who dressed diseased horse heels). He then outlined the theory that the cowpox infection prevented the smallpox infection. He used some examples of those he met in his practice who had had a cowpox infection, on whom inoculation (deliberate infection with smallpox) would not ‘take’. The failure of inoculation to take was interpreted as immunity to smallpox. He also outlined his test on James Phipps, first inserting cowpox matter and several weeks later performing inoculation on the boy. As the inoculation did not take Jenner interpreted this as proof of immunity.

The Royal Society rejected Jenner’s paper. They believed it did not have enough evidence to support it and that it might tarnish Jenner’s reputation. Jenner was still determined to publish, so he added more evidence – increasing the number of cases of vaccination. (A detailed discussion of the differences between Jenner’s first and second versions of the paper can be found in Crookshank’s book). He published it in 1798.

Pearson and Woodville

Two important figures took up Jenner’s vaccination idea, George Pearson and William Woodville. Both these doctors were vital in spreading the practise of vaccination and backing it ideologically.

William Woodville was the lead doctor at the Smallpox Hospital in London, so it can be imagined that he had significant influence over the treatment and prevention of smallpox. He took to the idea of vaccination and ran a significant number of tests. Woodville’s tests had many flaws, in particular that he sometimes attempted cowpox and smallpox inoculation very close together. However his testing was more extensive and better documented than Jenner’s.

Pearson sought to set up an institute for vaccination. This annoyed Jenner, as he was not consulted in advance regarding the project. Pearson also distributed vaccine lymph early on in the process to allow other doctors to perform vaccination, which was important as Jenner did not have vaccine lymph to give out on many occasions.

Jenner had a significant number of supporters in the medical profession. When he was put forward for a government reward in 1802, a large number of doctors spoke in his favour. The profession adopted Jenner’s theory very quickly, and it spread widely. This included across Europe, the United States, as well as many colonised countries.

Jenner’s Critics

Jenner had three main critics of his theory when it was first published. These three men were Benjamin Moseley, John Birch, and William Rowley. None of these men were antivaccination in the sense that we would understand this term today, i.e. they were not opposed to all artificial inculcating of disease. They were supporters of the old method of inoculation and sceptical of Jenner’s attempt to replace it. At this time, there were no high profile critics of both inoculation and vaccination (this tendency would only develop post vaccination mandate, from 1853).

These three men opposed the award to Jenner by the British government during the hearing on this issue in 1802.

Benjamin Moseley

Moseley was a doctor who was well known for other writings prior to his involvement in the vaccination controversy, in particular writings relating to the Caribbean.

He opposed Jenner’s method early on, and published more than one book relating to the issue. He considered that a ‘cowpox mania’ had taken over the medical profession. In his book, A Treatise on the Luis Bovilla, Or Cow Pox, he made several arguments. He stated there was no affinity between cowpox and smallpox, so there was no specific property of cowpox which meant it could prevent smallpox. He also argued that cowpox was not necessarily a mild disease. He pointed to the ulceration that often accompanied the practise.

John Birch

John Birch was a surgeon who was opposed to vaccination. In his text, Serious Reasons for objecting to the Practice of Vaccination he discusses the Royal Commitee on Vaccination. He argued that there was a large number of vaccine failures but that most of these were not admitted, and that the Committee tried to soften the language by stating that these cases only apparently had cowpox.

William Rowley

William Rowley was an active practitioner of inoculation. As such it could be said that he had a degree of vested interest in defending the practise against the new threat of vaccination. He considered inoculation to be a very safe practise that rarely led to death when performed competently. Vaccination, on the other hand, he considered both dangerous and ineffective.

Rowley authored a work called ‘Cow Pox No Security Against Smallpox Infection‘. This book has been considered a target of mockery by vaccinationists due to a couple of the images included in the book. These images claimed to show vaccination injuries, but as Rowley had titled one of them ‘The Ox Faced Boy’ he was mocked for making a linkage between vaccination and people becoming bovine.

Rowley actually collected a large number of cases, including with address details so at the time they could be checked, of vaccination injury, death, and cases of smallpox after vaccination.

He also provides an extensive list of excuses used by vaccinationists to defend their theory. These included the theory of ‘spurious cowpox’, which was outlined by Jenner in his second essay on cowpox. The idea of a ‘real’ and a ‘spurious’ cowpox allowed any cases of failure to be assigned to a spurious vaccination. He also accused vaccinationists of misdiagnosis of cases of smallpox in vaccinated people. He also states that vaccinationists formulated the excuse that even if cowpox failed to prevent the disease, it made it milder.

Conclusion

Vaccination had some significant opposition. However, it is fair to say that it had very little ideological opposition at this time. Its opponents thought it was unsafe and ineffective but advocated the earlier practise of inoculation instead rather than rejecting both. Well founded ideological opposition to vaccination would have to wait until after 1853 – the year of the UK’s smallpox vaccine mandate.