A Brief History of British Antivaccinationism, Part 3.2: White, Creighton and Crookshank

Introduction

This series hopes to explore the history of British Antivaccinationism and Vaccine Scepticism. It is divided into 7 main eras: the period of Inoculation, 1721-1798; the introduction of vaccination, 1798-1853; the imposition of mandates, 1853-1898; the remaining history of the National Antivaccination League, 1898-1972; DTP Vaccine Scepticism 1972-1998; Andrew Wakefield and vaccines cause autism, 1998-2019, and Covid 19, 2020 to present. This section forms part 3.2 looking at three main antivaccinationists active in the late nineteenth century, William White, Charles Creighton, and Edgar Crookshank.

William White

White authored a book called Story of a Great Delusion in 1885, looking at the history of inoculation and vaccination from an antivaccinationist perspective. It covers the entire period from the introduction of inoculation up to what was then the present day.

The book is primarily a historical account and he goes into detail not just about Jenner but the research of other important vaccinationists, such as George Pearson, another notable doctor, and William Woodville, doctor at the Smallpox Hospital in London. It explores their tense relationships and goes into more detail about Jenner’s personality (he had a significant habit of falling out with those who mostly agreed with him).

He also goes into the history of the government role in vaccination, such as the provision of vaccine lymph by the National Vaccine Establishment, and how £3,000 was budgeted for lymph, as an attempt to spread vaccination among the poor. He argues that Jenner’s ability to argue with everyone was one factor why government intervention was necessary to ensure the continuation of vaccination, rather than a reliance on private institutions.

He covers the introduction of the vaccine mandate – essentially the increasing intertwining between vaccination and government – and the introduction of ideological vaccine resistance, such as the founding of The Anti Vaccinator pamphlet by John Pickering.

Throughout the book he does make some arguments explaining why vaccination is a flawed practice, such as that it simply exchanges one disease for another while not decreasing death rate and that vaccine compulsion is purely about medical industry profit, rather than effectiveness. White believed the ineffectiveness of vaccination had been well demonstrated by the mandate introduction in 1853.

Charles Creighton

Dr. Creighton was a physician of note in the late nineteenth century, who completed a famous work on the history of epidemics in Britain. He was primarily interested in medical history rather than being a practicing doctor.

The story of how Dr. Creighton became an antivaccinationist is rather interesting. He was approached by the Encyclopedia Britannica to write an article on ‘Vaccination’ for their new edition. Feeling it was only justified to research the topic if he was going to write about it, he did – and became an ardent antivaccinationist. Perhaps surprisingly, the Encyclopedia agreed to publish whatever he wrote, so that edition ended up containing an antivaccinationist account.

He wrote two books condemning vaccination in 1887 and 1889.

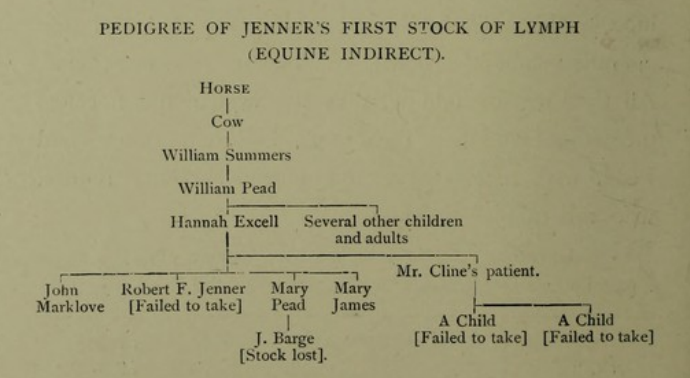

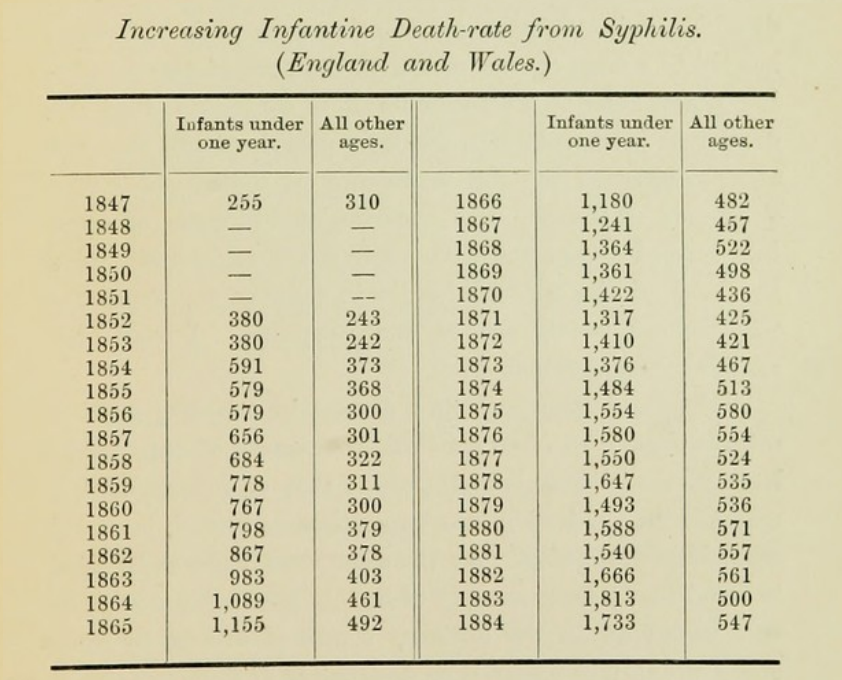

His book Cowpox and Vaccinal Syphilis goes into great detail on the topic of vaccine lymph. This included the historical disputes between Jenner and Woodville, and whether the two sources were equivalent. Jenner had issues obtaining cowpox lymph for vaccination, and this whole issue tied into the debate about ‘spurious cowpox’, which was one of Jenner’s excuses for vaccination failure. The primary argument in the book in terms of the dangers of vaccination is that cowpox is completely unlike smallpox, and is actually closer to syphilis (which was historically known also as ‘great pox’). There had been an increasing number of deaths from infantile syphilis after the vaccine mandate was introduced. In Creighton’s view, cowpox was causing this syphilis increase.

Jenner and Vaccination is a more general work on vaccination as a whole. He argues that Jenner used sleight of hand to redefine cowpox as variolae vaccinae (which literally means, cow smallpox). This manipulation led people to accept similarities between the two diseases that did not exist. Jenner also defined cowpox as a mild disease despite significant issues of ulceration to gain support for vaccination. He also argues that because Jenner used a very mild form of inoculation (deliberate infection with smallpox) to ‘test’ whether or not the vaccinated had immunity, this led to false claims of immunity. The mild (known as Suttonian, after Daniel Sutton) method of inoculation caused only a small effect anyway, so it having little to no effect after a cowpox inoculation proved nothing. He also mentioned the redefinition of smallpox as chickenpox after vaccination to avoid accusations of vaccine failure.

Creighton became involved in the National Anti-Vaccination League, and ended up being excluded from the mainstream medical community.

Edgar Crookshank

Crookshank published two volumes addressing vaccination in 1889. The second volume is a compilation of essays about vaccination and varying vaccination experiments performed by its advocates. As such we will focus on the first volume as that contains Crookshank’s actual arguments.

History and Pathology of Vaccination makes several arguments. One of the most interesting is Crookshank’s analysis of Jenner’s two different versions of his original paper on vaccination. Jenner originally tried to publish a paper on vaccination in 1796 via the Royal Society, but they rejected the paper. Instead, Jenner published the paper himself in 1798. There are significant differences between the two. Jenner did add more experiments and cases in an attempt to bolster his argument (the original paper had only contained the vaccination of James Phipps, one case). He also sought to tone down the negative effects of cowpox in the new paper, and attribute issues with the disease as incidental effects not directly caused by cowpox/vaccination.

A second argument made by Crookshank is to discuss all the different sources that were used as vaccine lymph, explored further in this post.

Conclusion

This period was the height of Britain’s history of resistance to vaccines, and this included the number and intelligence of those resisting vaccination. There are many critics who I have not covered, also active during this time, such as William Tebb and Alfred Russel Wallace. But there was more than intellectual resistance – there was popular resistance from the working class, the topic of the next article in this series.